Reading Sturgeon’s The Dreaming Jewels as a Nonbinary Allegory

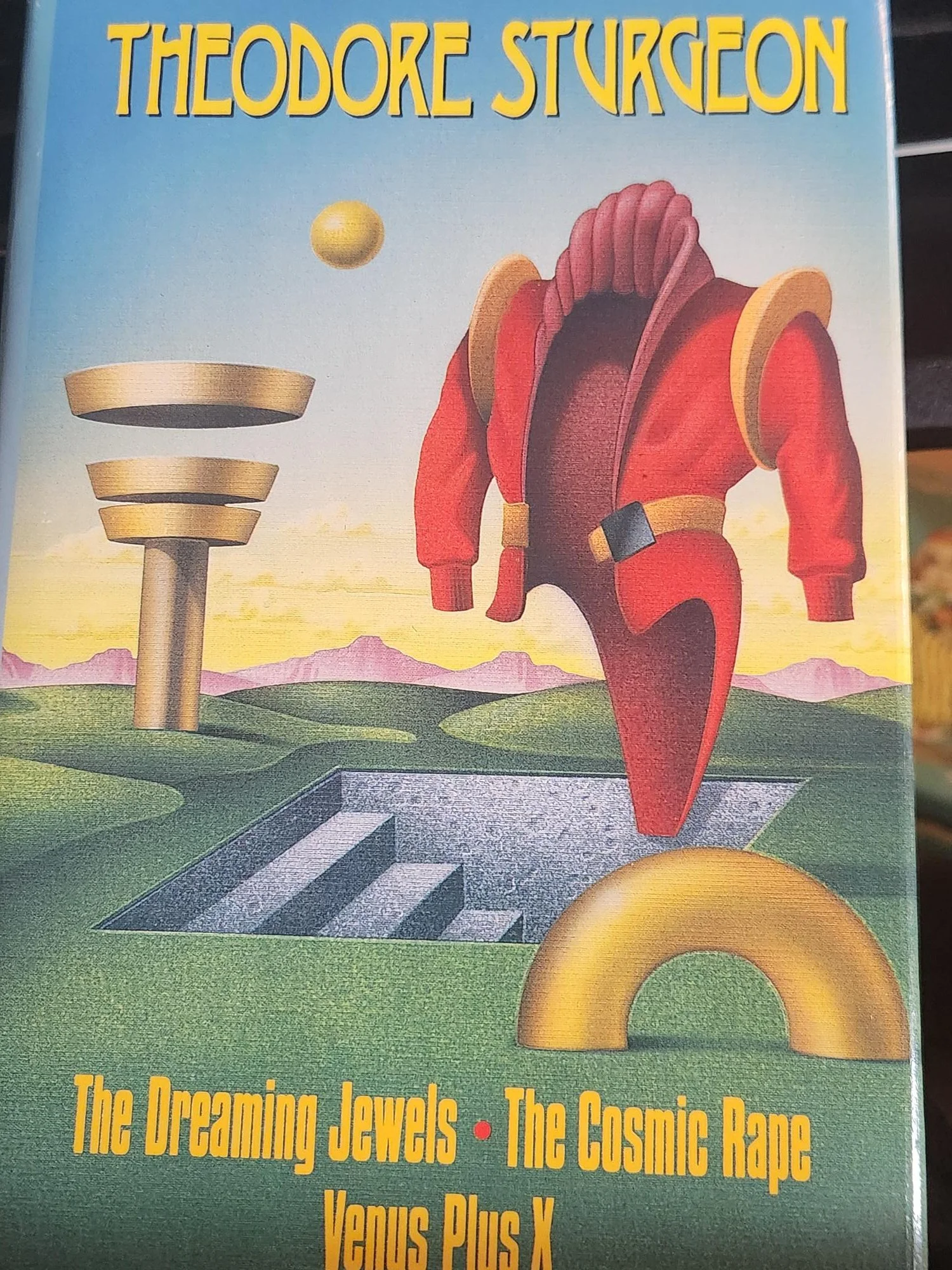

Recently I thought of a novel I read in my early 20s by Theodore Sturgeon: The Dreaming Jewels. The novel made a deep impression on me at the time, with its theme of becoming more human through reading. As an ADHD/autistic person, I have always loved the power of stories to connect me to others and help me grow as a person. When I first read the story, I remember being fascinated by the dreaming jewels themselves: aliens living among us and generating people with a different origin. When I looked up a synopsis of the story online, I was struck to see that the main character lives as a girl for ten years, something that I hadn’t remembered. Since, I have been recently been articulating my own nonbinary identity, I decided to read it again. I ordered the same Book of the Month Club edition that I read (The volume also includes Venus Plus X and The Cosmic Rape, which was published in an earlier, shorter form as “To Marry Medusa”). The book is Sturgeon's first novel, published in 1950. In his speculative fiction, Sturgeon reflected on gender, male/female relationships, as well as humanity's form and survival. For example, his novel More Than Human (which I haven't read) was an inspiration for the Wachowski's Sense8 series.

Gender stuff

I see the last two posts I published here were in November 2024, and both were gendery. I've been reading lots of memoirs, poetry, fiction by trans and nonbinary authors to better understand myself. I particularly resonated with what Judith Butler wrote in their book, Who's Afraid of Gender? In the book, they use the example of gender to show how failure to comply with gender norms can start one on the path of criticizing a dominant social ideology:

"at the beginning of life when we are generally called a girl or a boy, and we are suddenly placed in confrontation with a powerful interpellation from elsewhere. What sense is ultimately made of that interpellation cannot be determined in advance. We can, in fact, fail to live up to the demand that such a naming practice communicates— and that 'failure' may prove to be a liberation (Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, 2011). This is why our ability to criticize ideologies is rooted in the position of a bad or broken subject: someone who has failed to approximate the norms governing individuation, putting us in the difficult position of breaking with our own upbringing or formation in order to think critically in our own way, and to think anew, but also to become someone who does not fully comply with the expectations so often communicated through sex assignment at birth" (Who's Afraid of Gender, 14).

This notion of gender assignment as interpellation strongly resonates with me. From first grade onward, I felt this interpellation from classmates, friends, teachers, parents, and others. My friendships with guys have more often than not been an experience of being nudged toward gender norms. As early as first grade, a friend coached me to show up after school when a boy called me out. This interpellation continues to this day, when co-workers question why I wear a floral bucket hat or enjoy the Barbie movie. In the past few years, I have learned to stop hiding and enjoy gender joy. For example, I wore a colorful owl jeweled pin on my lapel for Christmas and a woman complimented me. I wore a scarf around my throat at church and a man said that he loved it. Lots of strangers love to see me wear my floral bucket hat. I find the experiences of trans people, especially women, to be helpful in thinking about gender, especially early conflicts between social interpellation and their own sense of themselves. At the same time, my sense of myself is different, that is, less binary. My own gender journey, I note with gratitude, resurfaced when my older daughter told me and my wife that she was trans. It opened a long-forgotten doorway within me.

My approach

I've been inspired myself by the trans allegory readings of Tilly Bridges at TillysTransTuesays.com, and I thought that I would take a similar approach to The Dreaming Jewels. You may note that one of the two posts from November 2024 was a review of Bridges’s book, Begin Transmission. was While her background is film making, mine is literature, and literature is hemmed about with skepticism regarding authorial intent as well as of allegorical writing and reading. Films, on the other hand, are based in drama, which has a long allegorical tradition. So, my approach will reflect a literary approach but absolutely includes the personal as well. I'll work through the story by summarizing key points, followed by a reflection on that part of the story, drawing out the allegory and making connections with my experience and that of others. Spoilers abound for this 75-year old book. It's a rich book, which also includes themes I won't discuss, like that of Zena's disability as a little person. There are certain overlaps between disability theory and queer theory which would make this discussion fruitful.

A note on names in The Dreaming Jewels:

Horton means "farm on muddy soil" (Wikipedia). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horton_(surname)

Hortense is a female form of the name, meaning gardener https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hortense

Bluett is a name from the Norman Conquest of England, possibly meaning blue eyed or wearing blue cloth. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluett

Armand is a French name, a form of Herman, meaning army man, or soldier. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herman_(name)

Tonta is a Spanish adjective meaning silly or stupid. It has a negative connotation and is related to the name Tonto from the Lone Ranger. https://www.spanishdict.com/translate/tonta

Kay Hallowell,

Kay is from Latin Gaius, meaning joy (or a name which is abbreviated from other names beginning with the letter K). https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Gaius#Latin

Hollowell is a compound word, meaning holy well.

Zena is of Greek origin. Xenia is the Greek rule of hospitality toward strangers, and Zena would suggest foreign. https://www.princeton.edu/~aford/terms.html

Pierre Monetre.

Pierre is a French form of Peter, meaning rock, but also the apostle gatekeeper of Christianity. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre

Monetre, is literally a French phrase, mon être: my being. Monetre is more often called Maneater because of his hatred for humanity.

Solum means base, bottom, soil https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/solum

Havana, named because he smokes cigars.

Bunny, named because she's albino.

Huddie, nickname for Hudson, as in the singer, Leadbelly. Hudson means son of Hugh. And Hugh means "heart, mind" https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Hugh

I'll use he/him pronouns for Horty throughout for clarity and in line with the text itself.

I. Within the Binary

The first part of the story happens within the binary, and it's not until this all falls apart that it moves beyond the binary.

Overview

To begin with, Horty is not human in origin. He is the child/ creation of nonbinary aliens, the "dreaming jewels," unicellular creatures which look like clear stones. These aliens do not compete with humans for resources, which is why they go unnoticed. People created by the jewels are either partial or complete. If partial, they are dependent on a model and may be deformed in some way. If complete, they can change their bodily form. They are shape changers who are not limited by the form given at birth. In this way, they are nonbinary like their parents, and they are transgender or genderfluid in their ability to change their form. Living creatures generated by these aliens have a formic acid deficiency, which they remedy by eating ants.

Summary: A difference seen as disgusting

The story begins when Horty's invisible difference is noticed by others at school.

"They caught the kid doing something disgusting under the bleachers at the high school stadium, and he was sent home from the grammar school across the street. He was eight years old then. He'd been doing it for years" (1).

We don't even know the kid's name yet and he's introduced as doing something disgusting. He knows that it's not typical, so he tries to hide it. From the perspective of the reader, Horty is introduced through the fact of his disgustingness to those around him. He's 8 years old. Before this incident he blended in as normal, but now everyone reacts as if he's terrible. His name is Horton "Horty" Bluett and his foster parents do not want to even hear him say what he did. His foster parents are Armand and Tonta Bluett. Eating ants is described as "disgusting," "nauseating," and his foster mother reacts with a "retching syllable." This disgust Horty is referred to by others as a "swine," a "filthy savage," a "sticky tongue," (anteater), and a pervert. Armand is concerned mainly with the reactions of others: kids, teachers, people in town. Armand mentions two possible career paths for Horty: one which Horty understands and one which horrifies Tonta. The reader is left to imagine what these options are. Armand calls Horty a symbol of his own failure and says that Horty won't be able to stay with him any longer. We find out later that Armand himself is not human but also a product of the dreaming jewels, so there is an implicit cause for this sense of personal failure.

Reflection:

So on the brink of puberty, Horty does something disgusting, something that he's done for years without anyone noticing. In the story, eating ants is the first visible marker for Horty's invisible difference. The disgust reaction to nonbinary gender will be familiar to anyone who's seen Ace Ventura, or other transphobic works. For me, I was six years old when a boy classmate told me that singing in the Christmas pageant was gay. For that boy, singing was a visible marker of my invisible difference. Fortunately for me, my dad told me that singing was good and that the boy was wrong. As a result, singing became a big part of my life, and I started to distrust gendered expectations.

The fact that Armand sees his own failing to meet the binary in Horty shows how the pressure to conform to binary results in intergenerational trauma. The narrowness of gendered expectations means that even cisgender people can fall short of expectations in their life and inflict it in turn on their children.

Like many queer kids, Horty is about to be kicked out of his house for embarrassing his parents. And like many queer kids, he is expected to work outside of society, unemployed, homeless, and/or a sex worker. Instead of leaning into his difference, however, and becoming more empathetic and more human, Armand survives by conforming to gendered expectations and treats Horty with a harshness that reflects his unexamined fear of being destroyed for what he is. Armand's name means "army man," a man who is who he is because he's been formed that way among other men to become a weapon of the state. Tonta is not even a name but an adjective meaning stupid or foolish; the story makes clear that over time she has changed to agree with Armand in all things, or to drink when she doesn't understand something. Tonta's gendered life is to annul herself in order to affirm her husband's way of thinking. For her, being a woman is a function of patriarchy.

Summary: Growing up trans or nonbinary

At this point we learn other details about Horty's childhood. Among his few possessions, he has Junky, a Jack-in-the-Box toy whose face looks like Punch, from the violent folk puppets: Punch and Judy. Junky has two gleaming jewels for eyes that are Horty's alien nonbinary parents. Armand refers to Horty's stuff as garbage, and Horty realizes that his clothes aren't even his. They are signs of Armand's social position. In addition, Horty's bedroom doesn't have a door because Armand believes that privacy is bad for children. While talking with Junky (his parents) about his situation, Armand overhears and angrily steps on Junky's head. By stepping on Junky, he crushes the head and endangers Horty's parents, the jewels. When Horty fights back, Armand calls him homicidal and then tries to shove him in the closet, smashing three of Horty's fingers. When Armand goes to get medical help to protect his own reputation, Horty escapes. Horty escapes but sees his classmate, Kay Hallowell, who goes out of her way to tell Horty that she doesn't reject him for eating ants.

Reflection:

A number of things happen here. First, when Armand steps on the head, the gendered stereotype face of Horty's foster parents is weakened. After this incident, Horty will no longer have his binary foster parents, the Bluetts. This reflects the experience of many trans and gender non-conforming kids, who are rejected by their parents and must find other support instead. In my case, my dad had a broad sense of male gender, which expanded over time.

Second, Horty resists being put in the closet and is injured. Being put in the closet is what Tilly Bridges calls "supertext." What does it mean that he loses three fingers? It may be a kind of symbolic castration, and if so, it means that Armand rejects Horty as a reflection of his own male gender. In any case, the injury represents the wounds inflicted by family that is supposed to protect but harms instead. One time when growing up, our family made a family crest at a retreat. My section showed someone crying because I wanted to show that as a family we cry together and dad joked that those were just my tears. Even though I was not rejected as a person, I was nudged back toward the closet of not standing out in a gendered way.

Third, it is unusual for parents to deny children a bedroom door, if they have their own bedrooms. In her memoir, This Body I Wore, about her life as a transgender woman, Diana Goetsch recounts growing up without a lock on her door because her mother always wanted to monitor what she did, afraid of her daughter's identity. For her part, Goetsch desperately wanted a lock as part of the necessary privacy to discover and understand herself. In the story, Horty's lack of a bedroom door signals Armand's constant surveillance of Horty in order that he will not embarrass him by failing to conform to social norms. For my part, I had a wide latitude with privacy, but I also tended toward oversharing with my parents. My brother and I also shared a large bedroom, divided by a solid wall with open spaces at the top. Childhood privacy has grown over my lifetime, and I see that as a positive development. Despite the development of childhood privacy, there is always another standard in play when parents are afraid of gender nonconformity.

Fourth, in the story, Horty's clothing is a sign of Armand's status. Just as in the experience of nonbinary and trans people, clothing is often an early expression of difference and policed by parents and schools for gender conformity. Clothing is often less about personal expression and more about social and gender norms. In my late 30s, I was interested in getting a solid silk shirt and dad discouraged me because he said that it would make me look like a mobster, i.e. someone outside of polite society.

Fifth, Kay Hallowell is a bright spot in his early life. I remember my friendships with girls in grade school as being life giving, and it is no wonder that Kay's names mean 'joy' and 'holy well.' About female friendship, Diana Goetsch says:

"In the culture in which I grew up, these two goals— to live in my gender, and female companionship— were incompatible. If any of my relationships had worked out, I might never have come out to myself" (This Body I Wore, Epilogue).

As a late blooming nonbinary person myself, I feel as if my marriage may have delayed my coming out, but it also gave me a safe place to be myself and articulate who I am.

Summary: A new life, a new gender

Horty jumps on the back of a truck and joins a carnival, and along the way, Junky's face is completely destroyed, leaving only the jewels. Here, he is educated by Zena and protected from Pierre Monetre, the leader of the carnival. He has a found family of sorts and new parental figures. In place of the foolish Tonta, Zena educates Horty in the depths of humanity through books and music. In order to give Horty a place in the carnival, Zena feminizes his name to Hortense and tells Monetre that Horty is her female cousin kicked out because her parents found out that Horty was a little person like Zena. Monetre is filled with hate like Armand, but instead of conforming to society rejects and undermines it. Monetre knows about the jewels and uses their incomplete creatures to make money and to hurt humanity. Monetre would like to use Horty to attack humanity as well, but Zena keeps Monetre from learning about Horty's identity. When Havana hears that Horty got in trouble for eating ants, he checks to see if Horty wants to work as a geek, someone who will eat weird things to entertain the crowds, but instead Horty finds employment as a singer performing with Zena. Although Horty is now Hortense, most people call him Kiddo. When Bunny sees Horty's makeover, she says "he's beautiful" and Zena immediate corrects her to say "she." The narrator even corrects their own pronouns for Horty/Kiddo from he to she. Horty's education is not limited to gender, but includes music, literature, speculative fiction, science, and the curious truth-is-stranger-than-fiction examples of Charles Fort.

Reflection:

Like many people who come out of the closet at variance with their assigned gender at birth, Horty moves to a new town where nobody knows him. In a self-fulfilling prophecy of the fears of Armand and Tonta, Horty takes a job outside of society in the carnival. He then begins living as a girl: girl clothing, girl name, she/her pronouns, and a new style of walking with smaller steps. The most astonishing thing about this change is that Horty is not bothered by it at all (and neither is he excited by it). In my personal experience, I find it interesting that Horty has a beautiful singing voice. As with my experience in grade school, singing is something that opens up for Horty once he stops living according to rigid gender stereotypes. Once allowed to live as ourselves, our lives often become broader and richer as well. I will note that the found family of the carnival, like other found families, is not without its risks. Sometimes people leave abusive families and find themselves with others who treat them poorly as well.

Summary: chasers, passing, and transmedicalism

Horty's hand is bandaged by Monetre, a former doctor. But later, his fingers grow back, which Zena has him hide from Monetre, so that he doesn't find out that Horty is someone created by the crystals. Zena knows that Monetre feels entitled to collect and make money off of people created by the creatures. She also has a long-term (non-sexual) relationship with Monetre, in which he uses her as a sounding board. But she fears Monetre, especially for Horty's sake. One time, Horty jokes to Huddie, a carnival worker, that his fingers would grow back if they got cut off. Because of Horty’s lapse, Zena causes Huddie to be fired from the carnival. Monetre likes to collect people created by creatures for his own agenda. Zena intuits that the more human Horty becomes, the less Monetre will be to dominate him. In addition to music and books, Zena encourages Horty in his affection for Kay Hollowell and his vengefulness toward Armand Bluett.

Reflection:

As with eating ants, growing back fingers is a marker of difference for Horty (he can be castrated but also grow it back, if you will). His life as a man ends with Armand's violence, and then he has to hide his regrown fingers so that Monetre won't know he's not like other women. While some people are hostile to those who are different, others are collectors, fetishizers, or chasers, like Monetre. The Maneater chases the crystal people and collects them. He has an extended personal (though non-sexual) relationship with Zena in which he uses her for emotional support and as a sounding board. He feels free to talk about his hateful plans for humanity with her because he does not regard her as a real person. As Tilly Bridges says,

"See the thing about chasers is that they never think about the feelings of the women they fetishize. That’s literally what fetishizing us is, right? Thinking of us only as objects you can use to get your rocks off" (emphasis in original). https://www.tillystranstuesdays.com/2025/02/25/ask-tilly-anything-part-5/

Zena regards Horty passing as female as a survival issue. Passing as female was also the standard medical guidance for transgender people through the 1980s. See https://www.tillystranstuesdays.com/2024/08/22/transmedicalism-and-wpath-version-1/.

While Zena's fostering of Horty's feelings is for the sake of his humanity, it's also something that encourages him to pass as a man after leaving the carnival. She confuses being human with social gendered norms. Zena sets him toward pursuing romance with his childhood friend, Kay, (sacrificing her own feelings for Horty) and competing with Armand, his foster father, to live as his assigned gender at birth. Nonbinary folks can pass for years, but passing is not living life to the fulness.

Summary: Sturgeon answers new theories from the Vatican ahead of time.

Horty lives as a girl for 9 years and doesn't grow. As a shape-changer, his form is determined by his mindset. In the story, Zena remarks about Horty:

"'Cogito ergo sum— I think, therefore I am.'" Horty is the essence of that saying. When he was a [little person] he believed he was a [little person]. He didn't grow. He never thought about his voice changing. He never thought about applying what he learned to himself; he let me make all his decisions for him. He digested everything he learned in a reservoir with no outlet, and it never touched him until he decided himself that it was time to use it."

Reflection:

It's as if Horty is on puberty blockers for 9 years. His adolescence is delayed with no sudden drastic changes brought on by hormones. Horty's cogito is contrasted with the mon être of the Maneater. Whereas Monetre affirms his own being by rejecting humanity and twisting the dreaming jewels to his hateful will, Horty is a creature of reason. The changes or lack of changes to his body are an expression of who he is, and who he has become through all of his education in music, art, science, as well as "the joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties" of humanity. I'm deliberately quoting the Second Vatican Council of the Catholic Church here, because the issue is one of humanity.(https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html).

As a Catholic myself, I am well aware of the Church's recent bursts of phantasmic fear (see Who's Afraid of Gender?, Butler, 6-7 with quotes from Francis the Pope comparing transgender people to nuclear weapons or Hitler Youth).

More recently, the Vatican has advanced another theory regarding transgender people:

"Desiring a personal self-determination, as gender theory prescribes, apart from this fundamental truth that human life is a gift, amounts to a concession to the age-old temptation to make oneself God, entering into competition with the true God of love revealed to us in the Gospel." (Dignitas Infinita, paragraph 57)

Instead of the Vatican speculation, Sturgeon shows us that while Monetre is entangled in a hateful rivalry with the world, Horty receives it all as gift from his parents and Zena. Gender is an expression of his person, and mine as well.

2. Beyond the binary

Summary: The binary trajectory falls apart

In a few years, Horty grows to full adult stature and, following the trajectory laid out by Zena, lives as a man, making money as a guitar player for a club. He does not have a white collar job that Armand Bluett would find respectable, but he lives in a human way, listening to music, reading books, and playing guitar. Playing guitar in a club in his home town, he sees Armand trying to force Kay Hallowell into a sexual relationship. Horty tells Kay to make a date for the following night and gives her cash to leave town. The next night, Horty takes his revenge by transforming himself into Kay and putting on a wig (he can't grow hair instantly). Alone with Armand, He cuts off three of his fingers with a cleaver and tells Armand that the physical revenge for what he did to Horty will come later. Armand's fear makes him track down Kay, who has gone to find Horty at the carnival.

Horty had always been passive, but in acting out the script given by Zena, he flips it. Instead of taking his revenge in a manly way by confronting Armand man-to-man, he transes his gender to appear as a woman. He does not enact violence on Armand, but re-enacts the harm done to himself as a child, in order to make Armand remember. Although motivated by revenge, he wants Armand to realize the hurt he's caused. But by taking on the form of Kay, he puts her in danger. The revenge Horty takes is not entirely a stereotypical female revenge, but also has aspects of a stereotypical male one, in that he "protects" Kay from the truth and doesn't invite her to participate in her own liberation. It's worth noting as well that even though Horty has a beautiful singing voice, the novel does not say that he sings when he performs, only that he plays guitar. By living as according to the male gendered expectations, Horty has lost a source of joy for himself and others.

Summary: the risk and reward of being non-binary

Horty gets caught at the carnival because he wants to comfort Havana who is dying, and would love to hear Horty sing one last time. So, Horty sings in the beautiful voice of Kiddo as he did when he lived as a woman.

Reflection:

In grade school, when I had been called gay for singing, I had another male friend who was interested in science, and went on to a rewarding career in chemistry. At a class reunion a couple of years ago, he told me that my interest in science enabled him to follow his own interests, despite the gendered peer expectations of our working-class parochial grade school. Living the fulness of our human potential not only enriches our own lives but also helps cisgender people live beyond the often restrictive stereotypes of gender.

Summary: A resolution both nonbinary and heterosexual

At this point all hell breaks loose. It turns out that because Horty is a mature, completed creation of his true parents, the alien jewels, he is not vulnerable to their pain or destruction. Everybody ends up at the carnival: Armand, Kay, Zena, Monetre, etc. Monetre and Horty get into a psychic and physical battle. Zena thinks that Monetre is a crystal creature and tells Horty to learn from the crystals how to kill their creations. Horty delivers a killing blast. This ends up being a judgment day, which reveals who is and isn't a creation of the jewels. Zena dies, Armand dies, Solum appears to die but as a psychic is just stunned for a while. Monetre is actually human and does not die. Horty realizes he can direct Monetre's body to create a toxin, which kills him. Horty appeals to the crystals to revive Zena, using their own values of artistic creation in order to do so. After everything, Horty is ready to go back to his life as a guitar player, but Zena suggests that it would be better to take over for Monetre and repair the damage done by Monetre all over the country.

Reflection:

In the end, Horty doesn't integrate with society but remains at its margins, protecting the normal humans from the evils done by a human who affirmed his own being. In this way, it is reminiscent of Venus Plus X, in which the androgynously gendered Ledom keep themselves concealed from the world in order to restore the cishet human race to themselves after their wars and rivalries destroy them. In marrying Zena, he stays within "his own kind" as crystal creatures. He also stays within the heterosexual framework of man and woman. This may be why The Dreaming Jewels didn't attract the kind of attention which occasioned Sturgeon's infamous postscript to Venus Plus X, in which he announced that he "wears no silken sporran" like the Ledom, that is, he is not androgynously gendered.

While The Dreaming Jewels makes a passionate argument for the value of nonbinary folks for humanity as a whole, it does not in the end center nonbinary joy the way that some works today would. Nonbinary experience and joy are there in the details, but the conclusion is designed to reassure an audience which is less receptive to nonbinary gender.

At the same time, Horty and Zena are both creations of the crystals, and are thus polymorphic and essentially nonbinary. By inviting Horty to stay with her and the carnival and not return to his life as a guitar player, Zena proposes a richer and more meaningful life than simply surviving by passing. We know his solitary life as a guitar player, waiting for his life to begin. But Horty’s new life with the recreated Zena is a blank page. We are left to imagine for ourselves the possibilities of this couple, Horty and Zena: their accomplishments, their romance, and their happiness beyond the gender binary.

—

Postscript: I don't want to get too much into biographical details about Sturgeon but he did have long-term relations with women including three marriages and fathering seven children. During the time he lived with his stepfather, he had little privacy, because he did not have his own bedroom. He also felt that The Dreaming Jewels was marred because both Armand and Monetre were based on his stepfather (as a reader, I disagree). Despite the postscript to Venus Plus X (which treats androgyny and homosexuality as a single thing), Sturgeon himself recounted an early homosexual experience (see the autobiography section of Sturgeon's Wikipedia article https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Sturgeon). And his friend, Samuel R. Delany also described Sturgeon as bisexual ("Before and After Stonewall" https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/stonewall-before-and-after-an-interview-with-samuel-r-delany/).