Urgency, necessity, and the fairy tale of ‘The Ten Fairy Servants’: an ADHD story

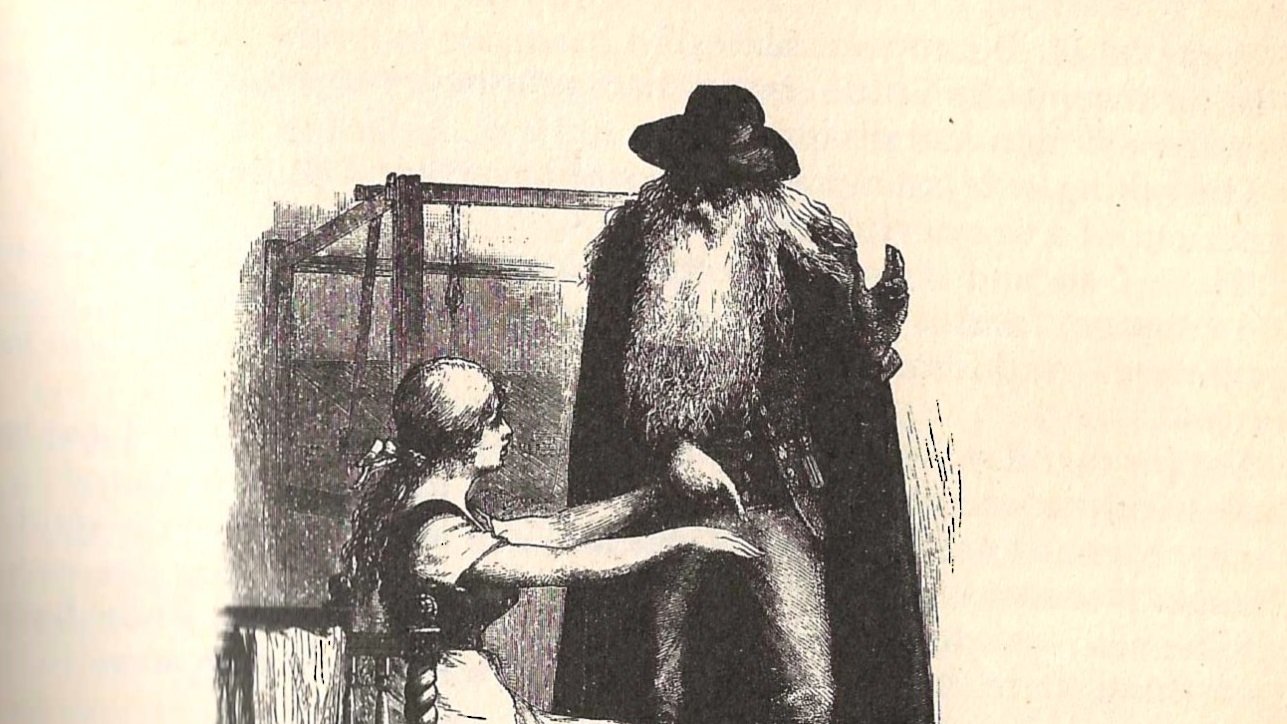

Detail from Ten Fairy Servants illustration from Scandinavian Folk & Fairy Tales

As I look back on my life from the perspective of a late-life ADHD diagnosis, certain experiences stand out. One of these experiences is the eureka I felt when reading the Scandinavian fairy tale, “The Ten Fairy Servants” (Scandinavian Folk & Fairy Tales, ed. Claire Booss, 265-268. A mostly similar version is online under the title ‘Stand the Toil’). When I first read this story, I saw it as expressing the surprising feeling of finding something easier to do when I learn that it is urgent or necessary. You could also read the story as moralistic or as a way of silencing women who complain about their workload, but for me, the main character, Elsa, is an everywoman and I see myself in her.

An aside about urgency and necessity: There are urgent appeals which are not necessary. And what is necessary is not always urgent. However, what is necessary always becomes urgent. In my mind, therefore, whatever is necessary takes on an urgency to me, and my preferred tactic is to handle it immediately.

To summarize the story, Elsa comes from a family of peasants, works in the city, and marries a well-off farmer. When the servants come in the morning asking her for things they need to get their jobs done, she is overwhelmed and has a meltdown, proclaiming:

“I will no longer endure this drudgery. Who could have thought that Gunner would make a common housewife of me, to wear my life out thus? Oh, unhappy me! Is there no one who can help and comfort a poor creature?”

At this point, a mysterious person appears who says that his name is ‘Old Man Hoberg.’ The way he describes himself, however, is in the form of a riddle:

“Your first ancestor bade me stand godfather to his first born. I could not be present at the christening, but I gave a suitable godfather’s present […] The silver I then gave was unfortunately a blessing for no one, for it begot only pride and laziness.”

Hoberg then gives her 10 funny little creatures who come out of his cloak and they start to tidy up the room. He asks her to put out her hands and the servants go into her fingers. After staring at her hands for a while, “she experienced a wonderful desire to work.” This feeling is then followed by results:

“‘Here I sit and dream,’ she burst forth with unusual cheerfulness and courage, ‘and it is already seven o’clock while outside all are waiting for me.’ And Elsa hastened out to superintend the occupations of her servants.“

The conclusion of the story supplies the answer to the riddle of Hoberg, who embodies necessity. “None was, however, more pleased and satisfied that the young wife herself, for whom work was now a necessity” Like Hoberg, necessity is a long-time companion of the human family and wealth has the impact of distancing us from necessity as when Hoberg was not present for a christening but sent silver in his place.

What stands out to me in this story is the change from something impossible to pleasant. The tasks were not manual labor, but getting things ready for the servants, like getting out haversacks so servants could get materials from the forest. When faced with necessity, or when necessity became insistent, the work became enjoyable. It was pleasing and satisfying. While there are some who would say that that Elsa resigned herself to being ‘happy’ in the face of necessity, that’s not what the story says, and that’s not my experience either.

My experience is that when I was in high school, I looked forward to the freedom of college as shown in such movies as Weird Science. When I got to college, I found it difficult if not impossible to finish projects, and do other required work. Even though I had a great interest in computer programming, that was not enough to get me through a class in Discrete Structures.

I intuited (for I had not read about the fairy servants yet), that if others depended upon me, I could learn basic living skills. I worked with L’Arche DC for a year. I helped others with their personal morning routines, cooking, and cleaning. I was also responsible for my own chores in the rotation as well. It was great that it wasn’t up to me to decide what things got done and when. But it worked! Necessity taught me to enjoy certain everyday tasks. I enjoy doing dishes and laundry (but putting things away involves more decision making and is more difficult). It also means that when evaluating job opportunities, I think about how close the job and the company are to needs, because necessity is something that is is good for me.

Update 1/18/2023

In 1882, Herman Hofberg published this story (The Ten Servants) in Svenska folksägner Volume 1. His notes say: “An old Gotland folk tale communicated by Mrs. D. Kindstrand, and in Fam-Journ. romantically treated by lecturer C. J. Bergman.”

Where the text refers to necessity, it uses the word behof (Old Swedish meaning need or requirement).

Apparently, Old Man Hoberg is the name of a friendly troll from another Swedish Fairy Tale. Somebody invites Hoberg to a christening in hopes of getting a godfather gift in abstentia. When Hoberg wants to come, the man inviting him scares him off by naming prominent guests, so Hoberg only gives the silver.

In Gotland, there’s a rock formation named Old Man Hoberg, named after the troll from the above story.

This article gives three sources for this other fairy tale about Old Man Hoberg.

"Hobersgubben" L. R. Weber (1836)

Jfr P. O. Backstrom: "Svenska folkbocker:, II (1848)

C. J. Bergman: "Gotlandska skildringar och minnen" (1882)

This appears to be the one referenced by Hofberg. This book has not only the godfather gift story but also a version of the ten fairy servants.